Sustainability reporting in the public sector: benefits and progress

Sustainability accounting and reporting can improve public sector performance but its uptake and evolution on the island of Ireland, both North and south, remains at an early stage.

Sustainability accounting and reporting (SAR) involves measuring, analysing and disclosing an organisation’s environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance to stakeholders with the aim of promoting transparency and informed decision-making.

SAR extends beyond traditional financial reporting and conventional financial metrics to provide a more complete picture of an organisation’s impact across emissions, the use of resources, employee conditions, engagement with the wider community and other outputs and activities.

SAR is important as it enables an organisation to demonstrate its commitment to sustainable development while also allowing stakeholders to make informed decisions about that organisation’s values and the potential risks it may face or present.

While sustainability policies often target the corporate sector, public sector organisations (PSOs) have been less studied in this context.

In contrast to the profit-driven private sector, SAR in the public sector is motivated by policy objectives such as social value and value for money.

The benefits of SAR include improved reputation, innovation and risk management, though challenges persist due to the voluntary, and sometimes inconsistent, nature of reporting practices and standards.

Public sector SAR: an all-island view

Both Northern Ireland (NI) and the Republic of Ireland (RoI) operate as parliamentary democracies with devolved powers affecting sustainability governance.

In NI, sustainability targets are set by the Climate Change Act (Northern Ireland) 2022 with the aim of achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

In RoI, the Climate Action and Low Carbon Development (Amendment) Act 2021 sets legally binding emissions reduction targets of 51 percent by 2030 and net zero by 2050. Both jurisdictions currently lack mandatory proforma for sustainability reporting, though RoI has more developed frameworks and mandates.

The research on which this article is based provides a comprehensive analysis of SAR practices in the public sector in both NI and ROI.

It explores the current state, challenges and opportunities of public sector SAR, with a focus on central government departments, local government, state-sponsored bodies (SSBs), higher education institutions (HEIs) and regulatory authorities.

Combining document content analysis of annual reports and semi-structured interviews, our study offers insights and recommendations for advancing public sector SAR in these jurisdictions.

Sustainability accounting and reporting frameworks

Sustainability accounting and reporting is guided by a range of internationally accepted frameworks, including:

• The Carbon Disclosure Project: The CDP focuses on environmental disclosures related to climate change risks.

• European Sustainability Reporting Standards: The ESRS are mandated for EU companies under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive, with there being recent proposals to delay and simplify their requirements.

• Global Reporting Initiative: The GRI modular framework emphasising multi-stakeholder perspectives which is widely used for sustainability reporting.

• International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Sustainability Disclosure Standards: Launched in 2023, and integrating the earlier work of organisations such as the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board and the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures, the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards provide a global baseline for investor-focused sustainability disclosures.

• International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board: The IPSASB develops public sector-specific sustainability standards tailored to government needs.

Public sector SAR: theoretical motivations

While it is accepted that PSOs may be motivated by a range of factors with regards to their SAR practices, our report draws on three key theories in detail to help explain SAR adoption in PSOs. These are:

• Legitimacy theory: This contends that PSOs disclose sustainability information to maintain societal legitimacy amid changing social norms.

• Stakeholder theory: This professes that PSOs respond to the demands of influential stakeholders, balancing varied mandates.

• Institutional theory: This asserts that PSOs adapt to legal, regulatory and cultural pressures through isomorphic behaviours (coercive, mimetic and normative).

– Coercive isomorphism explains how changing laws or regulations can force organisational change.

– Mimetic isomorphism contends that one organisation may simply copy the actions of another organisation (usually perceived as the lead or best).

– Normative isomorphism describes how actions may become widely adopted across organisations due to their acceptance as the best practice approach.

Public sector SAR: prior research

Prior research indicates that PSOs tend to focus more on environmental reporting than social or economic dimensions, with reporting often carried out in a fragmented and selective way in order to portray a positive image.

Larger PSOs, especially those with a commercial aspect or focus, tend to report more extensively than other PSOs due to visibility and funding pressures.

The GRI framework is most frequently used to assess public sector SAR, revealing uneven compliance and voluntary reporting, leading to selective disclosures.

Adoption of the Integrated Reporting Framework—part of the IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standards—is emerging but not yet in widespread use. Studies focus mostly on European PSOs, with HEIs and local government organisations being the most researched organisational types.

Research aims and methods

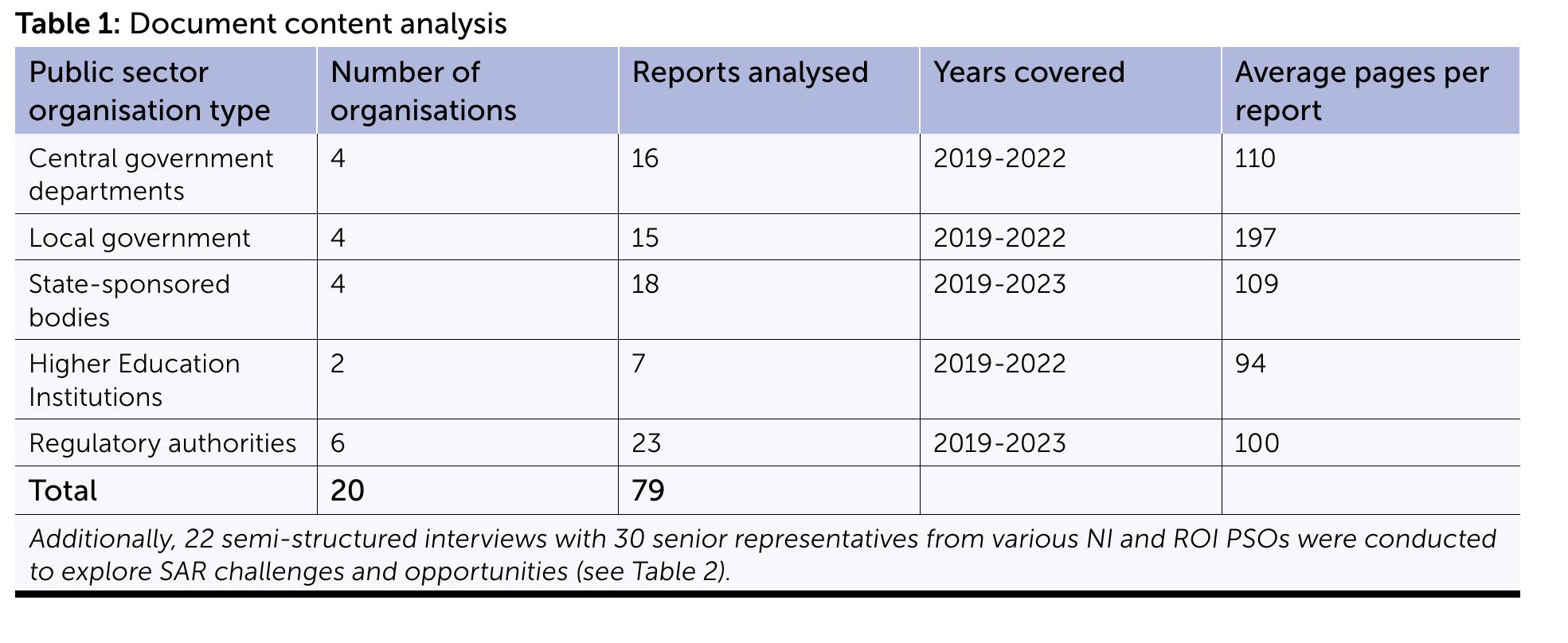

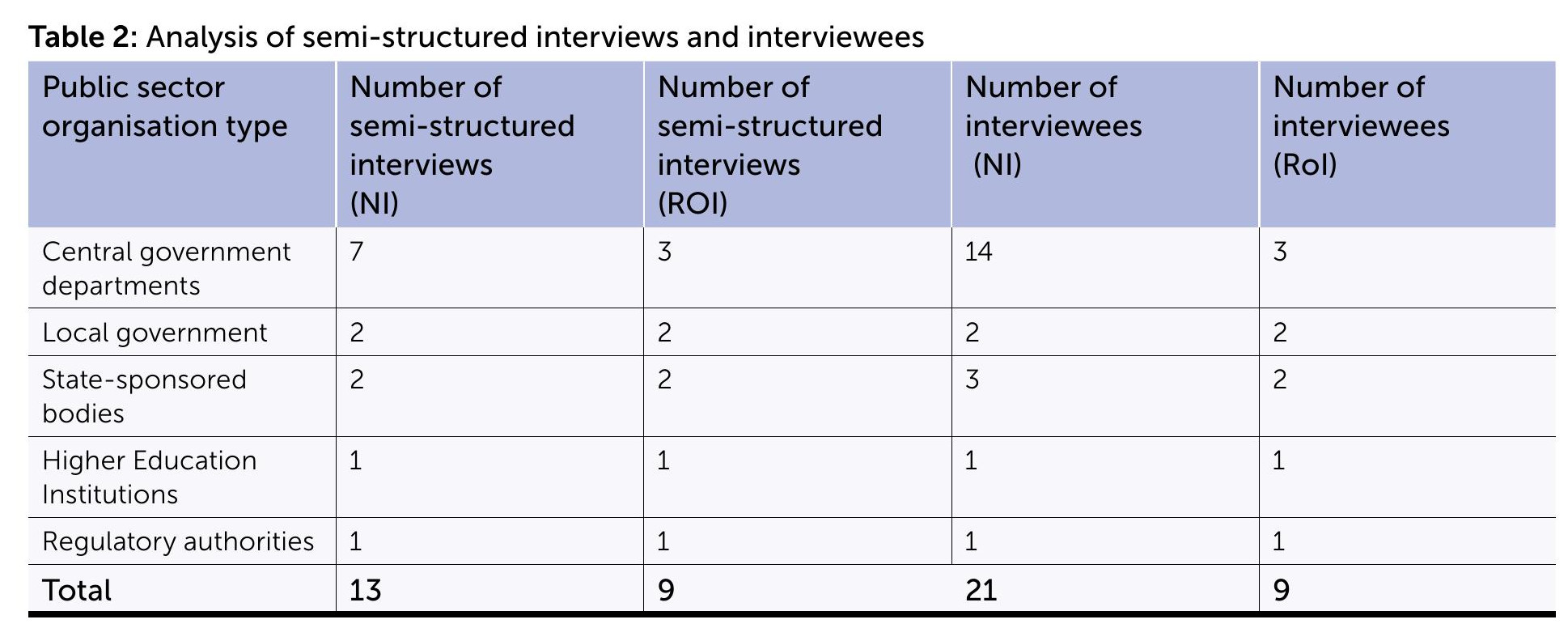

This study employed a longitudinal document content analysis of 79 annual reports from 20 PSOs (central government, local government, SSBs, HEIs and regulatory authorities), 10 from each of the NI and RoI public sectors for the years 2019-2022/23 (see Table 1).

The GRI G4 indicators were used to classify disclosures as economic, environmental or social, while NVIVO software facilitated qualitative analysis.

Document content analysis findings

The findings from the document content analysis (see Table 1) are summarised immediately below and in Table 3.

• A total of 26,764 references to 22 GRI indicators were identified.

• Social disclosures outnumbered environmental and economic disclosures overall.

• Local government organisations provided the highest number of disclosures, especially in the social and environmental categories.

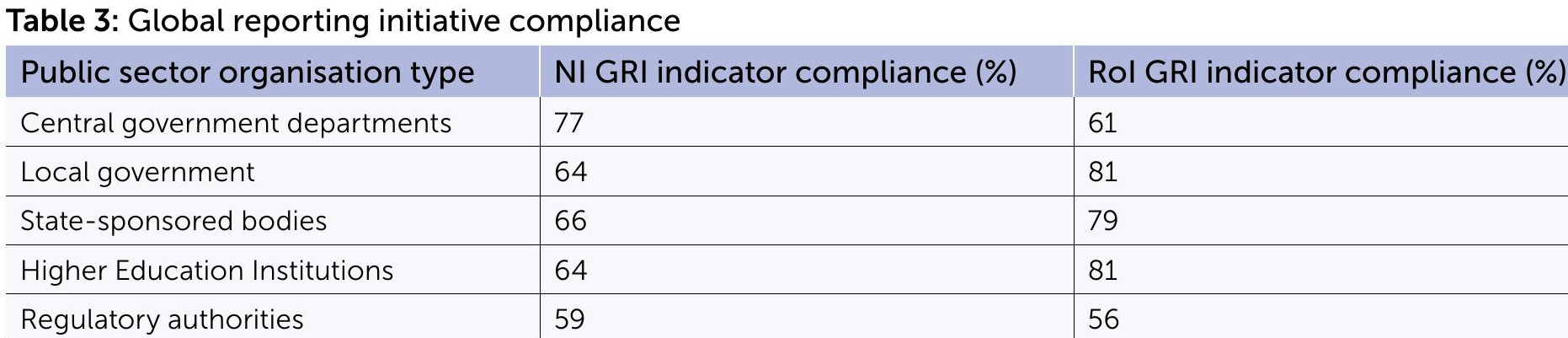

• NI central government departments showed the highest GRI compliance (77%), while regulatory authorities had the lowest (59%) (see Table 3).

• RoI PSOs accounted for 65% of all disclosures, indicating more mature SAR practices than their NI counterparts.

• In RoI, local government organisations, SSBs and HEIs had higher compliance (approximately 80%) compared to central government departments and regulatory authorities (approximately 58.5%) (see Table 3).

• Environmental performance disclosures (e.g. emissions and energy use) were most prevalent among SSBs, with regulatory authorities reporting little environmental data.

Semi-structured interview findings

The key themes arising from the semi-structured interviews (see Table 1) are summarised below.

1. Sustainability accounting and reporting practices by jurisdiction and organisation type

• SSBs have longer histories and more detailed SAR due to greater pressures.

• SAR in other PSOs is nascent, especially in NI, where reporting is less developed due to political factors (e.g. the absence of a functioning Executive between 2022-24).

• RoI benefits from more comprehensive guidance and mandatory reporting mandates (e.g. reporting to the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland).

• NI respondents reported slower progress but noted more recent efforts to develop sustainability metrics (e.g. carbon footprint and circular economy indicators).

2. Focus on environmental (climate) reporting

• Both jurisdictions prioritise environmental and climate-related reporting, particularly carbon emissions and waste management.

• SSBs embed sustainability in operations, including investment decisions considering environmental benefits.

• Social and other sustainability dimensions are recognised but less emphasised.

• The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive will increase data requirements and reporting scope in the RoI.

3. Drivers of sustainability accounting and reporting

• Legislative requirements, official mandates and external pressures (e.g. EU policies) are the primary drivers, with substantive voluntary reporting being unlikely.

• RoI PSOs follow specific mandates depending on organisation type (e.g. Climate Action Mandate for central government departments and Climate Action Framework for SSBs).

• Sustainability agendas are high priority but unevenly implemented.

4. Opportunities arising from sustainability accounting and reporting

• SAR encourages reflection on organisational roles in sustainability, promoting action and embedding sustainability objectives.

• SAR has the potential to provide performance management benefits and benchmarking opportunities.

• SAR may facilitate cross-border collaboration between NI and RoI PSOs on shared sustainability projects.

5. Challenges arising from sustainability accounting and reporting

• Fragmented and inconsistent guidance causes confusion.

• Data collection is complex, with there being difficulties measuring social and biodiversity aspects.

• Additional training and resources are needed, including greater sustainability accounting skills.

• Organisational culture and awareness vary, with evidence of some resistance to SAR.

• Financial and practical constraints hinder sustainability investments (e.g. cost of electric vehicles).

Conclusions and recommendations

By integrating ESG data with traditional accounting information, SAR supports better decision-making, enabling PSOs to benchmark their performance against others and plan future courses of action.

Allowing comparison across PSOs and regions also fosters continuous improvement through shared learning and innovation.

Placing sustainability at the heart of reporting signals its importance, helping to shift organisational culture and values. Public sector SAR is progressing in both NI and RoI, but the quality of implementation is still uneven and at an early stage.

PSOs in the RoI tend to display more advanced and comprehensive SAR than their NI counterparts, with local government organisations and SSBs leading on sustainability disclosures.

Generally, social and environmental issues dominate, while the economic elements of this reporting are less prevalent.

Legislative mandates and official policies are crucial for driving SAR adoption forward. However, fragmented guidance, training deficits and resource limitations present major challenges.

Our recommendations to advance SAR include:

• Fostering cross-border collaboration: sharing best practices, aligning priorities and developing standardised reporting templates to support a shared island approach to sustainability.

• Developing expertise: investing in staff development to improve reporting quality.

• Integrating SAR into financial planning: embedding sustainability goals and climate risk management into budgeting and risk frameworks.

• Reassessing placement of sustainability information: considering separate sustainability statements to enhance usability, as annual reports may not fully meet the needs of decision-makers.

Our report concludes that the evolution of meaningful SAR requires sustained leadership, harmonised frameworks, capacity building and cross-jurisdiction cooperation to embed sustainability into public sector governance and operations effectively.

The research report on which this article is based— Public sector sustainability accounting and reporting: an all-Ireland perspective—is authored, with support from Chartered Accountants Ireland Educational Trust, by:

• Ciaran Connolly, Honorary Professor of Accounting, Queen’s University Belfast.

• Paul Lawless, Analyst at Circana and PhD candidate at University of Limerick.

• Eoin Reeves, Professor, Department of Economics at University of Limerick and Director of the Privatisation and Public-Private Partnership Research Group.

• Elaine Stewart, Senior Lecturer in Accounting at Queen’s Business School, Queen’s University Belfast.